I confess to a long, profound love for rare books. I own many books about books: printing histories, catalogues of illuminated manuscripts, books about Elbert Hubbert and the Roycrofters, books about William Morris and the Kelmscott Press. It is a material infatuation. Here are five things I love about rare books:

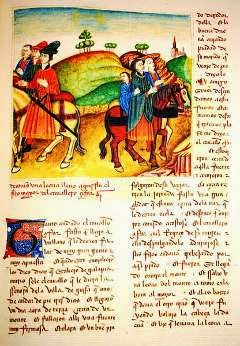

1) Illuminations

2) Engravings

3) Bindings

4) Typography

5) Curiously compelling content

Given my fangirling about books like this, is it any wonder that two of my favorite movies are

The Ninth Gate and

The Name of the Rose?

The first is a paranormal thriller, very loosely based on Arturo Pérez-Reverte's novel,

El Club Dumas.

In it, Johnny Depp is a disreputable antiquarian book dealer tasked to verify a rare demonology text. Death and all manner of wickedness ensue, as might be expected from a plot that has Lucifer as the co-writer of the antique text in question.

It is a mediocre and deeply silly film but, oh, the production.

It is filled with gorgeously bound books; a twisty New York basement bookstore I'd love to haunt; a beautifully poignant personal library on a bare floor in a once-grand residence that nevertheless is creepier than hell. And, of course, there's Johnny Depp in his prime, trying to solve an intellectual puzzle that ultimately defies reason.

The second movie is based on Umberto Eco's

The Name of the Rose — a mishmash of murder mystery, semiotic play and history lesson that manages to work as a narrative. The movie — like the Ninth Gate, mediocre —plays fast and free with Eco's novel in ways that are truly annoying, but at its heart is still the man of both reason and faith (Sean Connery, in

his prime, I'd argue) finding his way into a labyrinthine library that represents both an utter love of and utter fear of books.

That library. After picturing it in my mind's eye, I haunted antique stores for dusty armillary spheres, century-old engravings and, of course, the oldest books I could find (late 1700s was the best I could do).

What writer/reader wouldn't want to recreate some meander in that labyrinth?

In the Name of the Rose, Eco echoed (heh!) Jorge Luis Borges'

Library of Babel, whose randomly-organized library was the infinite universe and the search to make sense of its tomes (in the form of a grail-like index of books) leads to repression and destruction, intellectual and spiritual despair, and the unmet but ever beckoning promise of reason.

"The minotaur more than justifies the existence of the labyrinth," according to Borges' story "

Ibn-Hakim Al-Bohkari, Murdered in his Labyrinth." And the minotaur resident in both the Ninth Gate and the Name of the Rose sports one horn that bows to the power of books, and another that gores the acquisition, disposition and uses of such power.

So, perhaps these two thoroughly mediocre movies are more astute than I thought. Because, isn't every reader, every collector of books caught by that minotaur's horns?

Every writer, too.

"It is worth remembering that every writer begins with a naively physical notion of what art is," Borges writes. "A book for him or her is not an expression or a series of expressions, but literally a volume, a prism with six rectangular sides made of thin sheets of papers which should include a cover, an inside cover, an epigraph in italics, a preface, nine or ten parts with some verses at the beginning, a table of contents, an ex libris with an hourglass and a Latin phrase, a brief list of errata, some blank pages, a colophon and a publication notice: objects that are known to constitute the art of writing."

Who knew loving books could be so dangerous.

• • •

Want more antique book porn? The Smithsonian's Book of Books is for you. Click here for the Amazon listing. Or, do what I do, follow @Libroantiguo on Twitter. Some of the images in this blog post are from their timeline or their web site.